Ritualizing internally

The vedic yajña

Published in the magazine INDIKA of ELINEPA

Yajña: Exploring the meaning of inner sacrifice

By Katerina Vasilopoulou-Spitha

Deeply rooted in ancient Indian thought since the Vedic period was the concept of ritual (yajña). Etymologically derived from the verb root “yaj” whose meaning is attributed by Monier Williams Dictionary as “to worship, to honor, to offer”, the word “yajña” reveals the need of ancient Indian people to contact with the various facets they attributed to the Absolute One and recognized as their “gods” (deva-s).

Rituals provided the functional “language” through which, in alignment with the order (ṛta) that characterized all the mysteries of the universe, they could invoke the assistance of a divine power to fulfill a wish (for children, rain, cattle). The originator of the ritual act was the god of fire Agni, whose presence was required every time they lightened up the flame on the altar (kunda) of their yajñashala.

For the Indians of those times, behind each element of the ritual there was a symbol with the help of which they tried to form rather than to represent the intrinsically formless reality that constituted that Absolute One1.

The prominent role of rituals in Vedic society is confirmed by the Brāhmaṇas, texts in which the typical rituals of each religious ceremony, the duties of the priests as well as the hymns that must be chanted on each occasion are described with particular care2. From the information they convey to us, we can conclude that the rituals from the period of the 8th century BC3 were distinguished, on the one hand, by a complexity of such a degree that made necessary the assistance of a group of specialists and on the other hand, by numerical abundance, given that they were linked to every aspect of life and not only to some very special event or reason.

In this extended framework of religious practices, alongside the more formal and complex rituals, such as the horse sacrifice (Ashvamedha)4 , find their place the daily fire rituals (agnihotra), the rituals dedicated to the new moon and the full moon (dārśapaurṇamāsa), to the beginning of the seasons (spring, rains, autumn) (cāturmāsyāni) and to the harvest season with the offering of the first fruits (āgrayaṇa)5.

Sacrifice as an interpretive polyhedron

Interpretatively, the word “yajña” has come to have the meaning of sacrifice, a fact that according to some scholars needs further investigation. Pankaj J. in his article “Reinterpretating Yajña as Vedic Sacrifice” points out that the emphasis on the element of sacrifice has sidelined other important aspects of the role of yajña, such as that of strengthening the social and political bonds between the participants6 based on the need to function together, as a harmonious whole, even for a period of several days for the purposes of specific rituals.

Following a similar line of interpretation, R.L. Kashyap notes that the word “sacrifice” should not be associated with the feeling of regret or remorse that one has when is forced to abandon (“sacrifice”) a valuable thing or purpose for the sake of another purpose in his/her life. Basing his argument on the meaning of the two syllables of the word, “ya” which denotes “effort, struggle” and “jna” which has the meaning of “a thing considered sacred”, he translates as “yajña” the action of striving to acquire something sacred7.

The above statement emphatically highlights the type of offering and invocation that takes place during yajña. As for the first element, “dāna” (offering) is an act that the offeror proceeds with voluntarily (and not by compulsion), motivated by selfless, sattvic motives, that is, his tendency to think above his selfish interest 8. The “tapas” practices he engages in in order to purify (tap means “to make something hot by heating it”) the body, mind and speech from “toxic” emotions, actions and thoughts of all kinds, such as desire (kāma), anger (krodha), greed (lobha), delusion (moha), arrogance (mada) or jealousy (mātsarya) aim to ensure this specific type of offering.

On the other hand, the second, equally significant element that the present interpretation of the yajña emphasizes on is that the invocation of the offeror does not constitute a call by which the corresponding deity with her/her divine power will fulfill the proclaimed wish. The “reins” of the act are taken by the offeror alone, by infusing the power within himself/herself, after making sure that he/she becomes a “vessel” ready (with a clean, strong body and mind) to receive it.

The successful outcome of this effort is what could be described as “sacred,” “marvelous,” or “miraculous” about yajña. The term “sacrifice,” therefore, encompasses a set of concepts and practices that we are called upon to approach very carefully in order to conceive it in its entirety, avoiding, thus, to “color” it unilaterally or, possibly, completely incorrectly.

Sacrifice as an internal ritual

The power of the “yajña” is not based solely on the observance of a strict ritual protocol that required the performance of mainly external actions. It is not limited, in other words, to the various duties of the priests who take part, the appropriate recitation of the mantras that requires, among other things, correct knowledge of their pronunciation, or to the process of consecration (dīkṣā) of the initiator of the ritual (yagamāna) which involved his isolation from his surroundings and his bathing before receiving the fruits of the sacrifice offered.

Except from external (bāhya), yajña is primarily an internal (antar) action. That is, apart from its biological and socio-political symbolism which is evident in the motifs it employs to depict man’s relationship with his/her wider natural environment, the forces of nature, time and space, as well as with other people, yajña also has an internal symbolism, since it forms the field in which the performer is able to inquiry into his/her emotions, thoughts and ultimately his/her true self9.

In fact, no external sacrifice is considered complete, unless it is followed by an internal sacrifice. The former serves as the spark that lightens up an internal fire whose smoke will rise, just like the external one, penetrating all the intermediate places (lokas) until it reaches the divine layer.

The internal sacrifice, therefore, has primarily a transformative rather than worshipping content, insofar as it does not require the visualization of the deity and the making of offerings to it with the mind, just like a worshiper would do. The ultimate goal of the yagamāna is, in other words, by becoming himself/herself the offering to his/her altar (yūpa), to achieve an internal transformation of a magnitude capable of ensuring his/her spiritual awakening.

The ultimate goal of the yagamāna (offeror) is by becoming himself/herself the offering to his/her altar (yūpa), to achieve an internal transformation of a magnitude capable of ensuring his/her spiritual awakening.

The following texts through their references help to shed light on the nature of sacrifice as an internal ritual.

ṚG VEDA

The Puruṣha Sūkta is a hymn of the Ṛg Veda (10.90) which presents the mythical story of the creation of the universe by the supreme One described as Puruṣha. According to this sūkta, the cosmic totality was the body (pur) of Puruṣha, which it acquired inspired by its own creative will, as it became the ritual material in the first sacrifice ever performed that marked the beginning of everything.

According to the Puruṣha Sūkta, the entire universe (known and unknown), from the gods (devatas) and the galaxies to the beings of this world (animals, human existence) and its elements (sun, moon, seasons, earth, sky), is the result of its own self-sacrifice. In the light of this particular text, the act of internal sacrifice (yajña) on the part of the common offeror acquires a twofold meaning.

It declares his/her firm intention to tune in to his/her natural, existential destination by extending his/her knowledge beyond the manifested, the universe and himself/herself, towards the unmanifest, the soul (jīva) of all souls and source of all creation, the Absolute One. But also, following the cycle of creation, destruction and rebirth to which cosmic structures are endlessly subject, to recreate his/her own mental structures in order to benefit society, in line with the will of the One10.

In the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, the section of the Ṛg Veda attributed to the riṣhi Mahidāsa Aitareya, we find in the sacrifice of animals another extension of the internal sacrifice, as the animal that is killed serves essentially as a symbolism of the sacrifice of the animal instincts and passions of the yagamāna11.

Another part of the same Veda, the Sankhayana Āraṇyaka, describes the fire ritual (agnihotra) as a process that continues within man. Specifically, prāṇa, the vital air is the Āhavanīya altar (eastern fire), apāna the Gārhapatya altar (western fire), vyāna the Anvāhāryapacana altar (southern fire), the mind is the smoke, anger the flames, the teeth the burning coals, faith the water, speech the fuel, truth the offering and the knowing self the blissful essence, “rasa” (taste or sensation)12.

KRIṢHṆA YAJUR VEDA

In the Taittirīya Āraṇyaka, a section of the Kriṣhṇa Yajur Veda, another series of analogies between the various aspects of external and internal yajña is found. According to the first part (anuvāka) of the third section (prashna) (3.1.1), chitti (the function of thought) corresponds to the spoon (sruk) with which the offering is made, chitta (the mind) is the ghee of the offering (ājyam), vak (the subtle speech) is the altar of fire (vedi), adhitam (the words spoken) is the sacred grass where the gods sit (barhi), keto (the intuitive rays) is the hot flames of the fire (agni) on the altar, vijnata (the faculty of discrimination) is the fire (agni) that is lit on the altar, prāṇah (the vital energy) corresponds to the other offerings (havi) (such as firewood, rice), vakpati (the master of speech) is the hota priest, manas (the mind) is the priest who undertakes the chanting of the mantras (upavakta), the saman (the mantras) the priest in charge of the ceremony (adhvaryu)13.

UPANIṢAD-S

The Chāndogya Upaniṣad describes the journey of the soul as yajña. Soul is the yagamāna with the sensory organs of the body playing the role of the priests who gather to help it perform the yajña. According to the philosophical perspective of Chāndogya, all the actions (karmas) through which we “weave” the thread of our life are our offerings to this sacrifice. Therefore, all life is a sacrifice.

“When one hungers and thirsts and does not enjoy himself- that is a Preparatory Consecration Ceremony (diksa). When he eats, drinks, and enjoys himself – then he joins in the Upasada ceremonies. When one laughs and eats and practices sexual intercourse – then he joins in the Chant and Recitation. Austerity (tapas), alms-giving (dāna), uprightness (ārjana), harmlessness (ahimsā), truthfulness (satya)-these are one’s gifts for the priests.” 14

In the Mahānārayaṇa Upaniṣad, one of the minor Upaniṣads, we encounter a similar idea. In its last chapter, in particular, the journey of knowledge of the sannyāsi is presented as a sacrifice. He, the text states, is the man of knowledge whose faith is his wife, his body is the sacred fuel (idhma), his chest is the place (yūpa) of sacrifice, his lock of hair the sacrificial broom, his love the sacred ghee (purified butter), his speech is the priest Hotṛ (the hymnist of the Ṛg Veda), his breath the priest Udgātṛ (the hymnist of the Sāma Veda), his eyes the priest Adhvaryu (the hymnist of the Yajur Veda), his mind the object of his worship, his knowledge is his sacrifice. 15

Examples in yogic practice

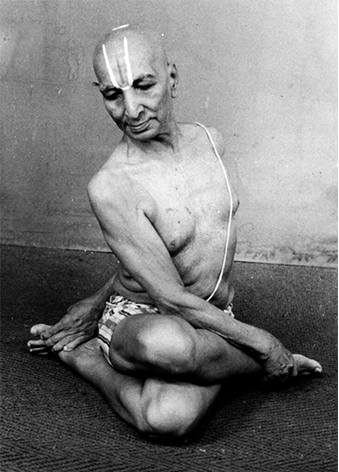

The great “father of modern yoga” Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888-1989) emphasized in his teachings, as we learn from his student A.G. Mohan16 , the importance of two daily, ritualistic practices, the practice of “Salutation to the Divine at sunrise and sunset” (“sandhyāvandana17”) and prāṇa agnihotra bhāvana. The former, which includes the practices of prāṇāyāma and meditation on the gāyatrī mantra, was, according to Mohan’s testimony, often recommended by Krishnamacharya to his students as a means of strengthening their will against sluggishness (styāna), doubt (saṁśaya), negligence (pramāda) and the other physical and mental obstacles listed in the Yoga Sutra (sutra I.30).

It is a practice in which we can identify many of the elements of the Vedic esoteric yajña, such as the element of internal symbolism (the external sun here symbolizes the light of consciousness), the stress laid upon the sattvic intention of the practitioner to enlighten his/her mind, as well as the purifying and transformative effect of the entire ritual process, as the practitioner, having destroyed the impurities through pranayama and the old latent impressions (saṃskāras) through the gāyatrī mantra, transforms himself/herself into a new person by meditating on the mantra.

The practice of “Salutation to the Divine at sunrise and sunset” (“sandhyāvandana”) was often recommended by Krishnamacharya to his disciples as a means of strengthening their will against the obstacles listed in the Yoga Sutra (sutra I.30).

The prāṇa agnihotra bhāvana is another esoteric ritual in which the practitioner makes an offering to the prāṇa, the vital energy in him/her. According to Krishnamacharya, each of the following functions of prāṇa performs the role of each of the factors of the Vedic yajña: the prāṇa vāyu the priest Hotr, the samāna vāyu the priest Adhvaryu, the udāna vāyu the priest Udgātṛ and the vyāna vāyu the priest Bramhā (the hymnist of the Atharva Veda and the general supervisor). The apāna vāyu has the role of the wife (patni), who attends the ceremony in a supportive manner, activating in its upward movement the agni (digestive fire) in order to process the offered food. Finally, the offeror (yagamāna) is the mind (manas) itself.

“Yajñā is the external symbol of the internal work…It is at the same time

a battle against inner, dark forces, an ascension

to the highest mountain peaks beyond the earth, and a journey

on the other shore, in the most distant infinity”.

S.K. Ramachandra Rao

Notes

[1] Smith, KB, Reflections on Resemblance, Ritual and Religion, Oxford University Press, 1988, p.50-51

[2] Theotokis, K., History of Indian Literature, National Bank Educational Foundation, Athens 1993, p. 38

[3] Olivelle, P., Upaniṣads, Oxford University Press, 1996, p.xli

[4]The purpose of the Ashvamedha was primarily political, as it was intended to confirm the king’s right to rule. Talbott R.F. gives us a detailed description of the complexity of a public, formal (śrauta) ritual such as this, which included the lighting of three fires and the presence of a large group of specialized priests, up to 16 in number. See Talbott R.F., Sacred Sacrifice: Ritual Paradigms in Vedic Religion and Early Christianity, Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1995, pp. 107-166

[5] Jamison, SW, Witzel, M., Vedic Hinduism (ebook), Harvard University, 1992, p. 39

[6] Pankaj, J., “Reinterpreting Yajña as Vedic Sacrifice”, Brahmavidya: Adyar Library Bulletin, 2011, p. 161-178

[7] As an example of the application of this particular interpretative prism, Kashyap R.L. uses the term “jñāna yajña” of the Bhagavad Gītā which, according to him, could not imply renunciation but rather the intensive effort of the seeker to acquire sacred knowledge (jñāna). See Kashyap R.L., Inner Yajna for all-around perfection, SAKSHI, Bengaluru, 2018, p.5

[8]Real effect on the invocation of the offeror can only have a sattvic offering rather than any other (rajasic or tamasic) type. See Gyanshruti, S., Srividyananda, S., Yajna: A Comprehensive Survey, Yoga Publications Trust, Bihar India, 2006, p.79

[9] Choudhuri, U., “Vedic Ritual and its Symbolism”, World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues, vol.6, no 1, 2002, p.198.

[10] Gyanshruti, S., Srividyananda, S., Yajna: A Comprehensive Survey, Yoga Publications Trust, Bihar India, 2006, p.199

[11] Choudhuri, U., “Vedic Ritual and its Symbolism”, World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues, vol.6, no 1, 2002, p. 202

[12] Choudhuri, U., op. cit., p.200

[13] Kashyap, R.L., Taittirīya Āraṇyaka (Kriṣhṇa Yajur Veda): Part I, SAKSHI Trust, 2014, p. 187-188

[14]”When one hungers and thirsts and does not enjoy himself- that is a Preparatory Consecration Ceremony (diksa). When he eats, drinks, and enjoys himself – then he joins in the Upasada ceremonies. When one laughs and eats and practices sexual intercourse – then he joins in the Chant and Recitation. Austerity (tapas), alms-giving (dāna), uprightness (ārjana), harmlessness (ahimsā), truthfulness (satya)-these are one’s gifts for the priests.”, Chāndogya Upaniṣad (3: 17, 1-4). See Hume, R.E., The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, 1921, p.212

[15] Deussen, P., Sixty Upanisads of the Veda (Part I), Montilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1997

[16]For more details on the above ritual practices, see Mohan, A.G., Mohan, G., Krishnamacharya in his own words: Asana, Pranayama, Meditation, Mantra, Ritual, Ayuverda, Svastha Yoga, 2022, pp. 79-82 and 87-88.

[17] The word “sandhyā” generally refers to the time when night becomes day (when the sun rises) and day becomes night (when the sun sets). Krishnamacharya adds a third time, when the sun reaches its highest point at noon.