The nature of desire

From Epicurus to Patañjali

Published in the magazine INDIKA of ELINEPA

(Last edited 2024)

True pleasure does not come from an unconditional surrender to sensual pleasure but from a process of reflection on the nature of desire, which is based on the principles of moderation and self-sufficiency, Epicurus teaches us. Similar is the idea that forms the basis for the practice of Patañjali’s yoga student in continence (“brahmacharya”) and non-greediness (“aparigraha”). A key pillar of the individual’s path to happiness seems to be for both philosophers the perception of philosophy as therapy and art of ethical living.

Epicurean philosophy converses with Patañjali’s yoga philosophy

By Katerina Vasilopoulou-Spitha

Pleasure and pain

As “pleasure” is defined in epicurean philosophy the internal delight that comes from the complete absence of physical pain (aponia) and mental disturbance (ataraxia) and forms part of the relationship between man and the world around him. This means that the innate tendency towards pleasure, far from being a superficial surrender to sensual pleasure, signifies in Epicurus man’s endeavor to master the influences of the external world.

Those influences, which man experiences as psychological disturbances and pain (algos), are manifested in the form of desires, passions and emotions.

In lieu of an unrestrained cult of pleasure, Epicurus proposes the qualitative distinction of desires that is based on a process of contemplation on the nature of desire itself which reveals the cause of every choice and its avoidance and constitutes, in essence, a study of human nature and its needs.1

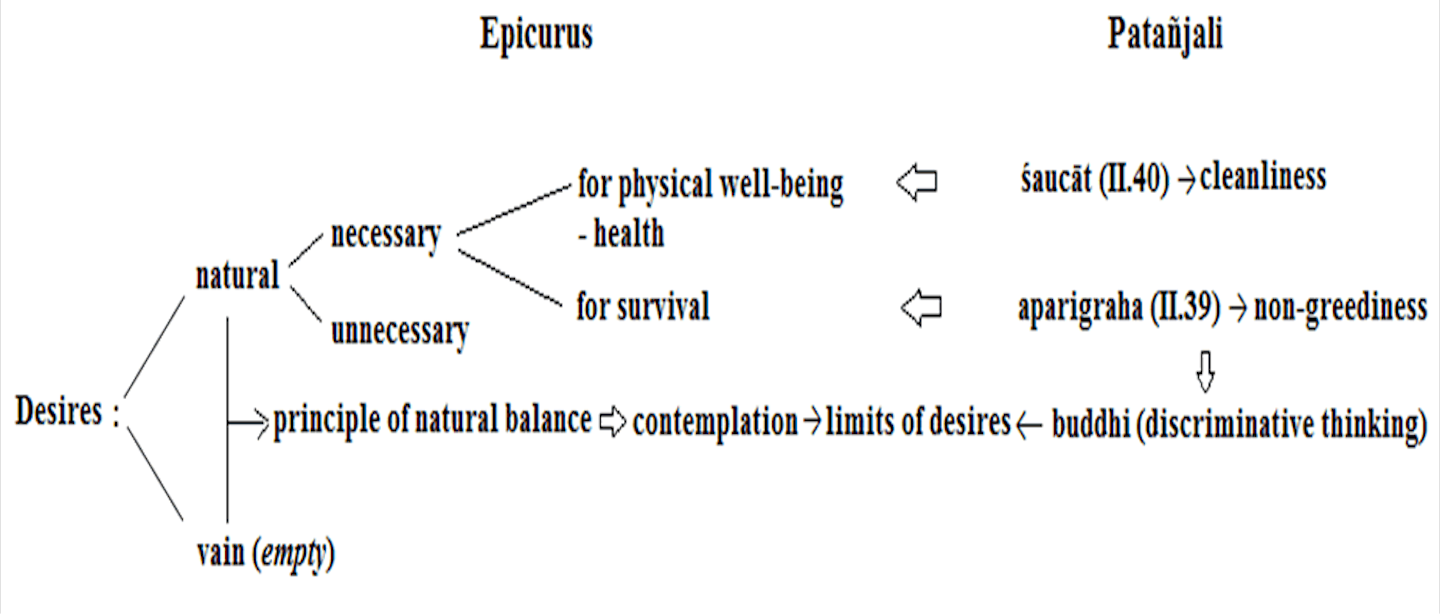

Basic criterion for distinguishing desire into natural and vain (empty), natural and necessary, and natural and unnecessary is natural balance.2

This principle defines according to Epicurus the limits (perata) of the extent of desire which he places within the context of the body’s natural needs, conceived as substance that is subject to the bonds of matter (needs for survival), yet whose destination is also to evolve and to prosper (needs for bodily well-being, health). In this respect, thirst, hunger or clothing are necessary for man’s survival and therefore, natural and necessary, in contrast to wealth and luxury which are vain (empty), since they are based on the vain opinion (kenodoxia) that they can satisfy a real need and remain unsatisfied due to the absence of limitation for their acquisition.

Being one of the five afflictions (kleśa-s) that disturbs the balance of consciousness, pleasure (sukha) in Patañjali and the yoga philosophy is thought to lead to desire and emotional attachment (sūtra II.7). 3

As it appears, pleasure comprises the element of pain as result of the attachment that derives from greediness and passion which constantly grow, since one craves increasingly for more. For an ancient Indian philosopher like him, desire (vāsanā) forms an integral part of human existence from the beginning of time, when human, caught in the web of nature, became prey of the polarities of pleasure and pain, evil and good, permanent and impermanent.

Although both philosophers identify pleasure with satisfaction, the starting point of their philosophical thought seems to be largely different. In fact, in Epicurus pleasure is associated with the absence of pain (aponia) and mental disturbance (ataraxia), whereas in Patañjali with emotional attachment and, ultimately, pain. Accordingly, for Epicurus pleasure presupposes the absence of pain, wherein for Patañjali its presence.

Pleasure for Epicurus presupposes the absence of pain (aponia) and agitation (ataraksia), while for Patañjali, their presence.

With regard to mental tranquility, we are able to attest a relevance between the blissful sobriety of the epicurean mind and Patañjali’s view of peaceful mind, although pleasure in Patañjali is not synonymous to tranquility like in Epicurus. Already in the first chapter (samādhi pāda) of his work, Patañjali defines yoga as the restraint of the fluctuations of consciousness that leads to a sattvic state of profound silence and finally to (samādhi).

Even though the maximization of the sattvic quality, perceived as wisdom, peace and happiness, against the other qualities of nature (rajas and tamas) is essential for the yogi, that kind of happiness is related to the material world, unlike the ultimate experience that comes from realizing the soul (puruṣa) and perceiving pure being.4

Hence, the peaceful mind may be a common point of reference in both Epicurus and Patañjali, yet in Epicurus it is presented as the end, while in Patañjali as the means towards the end, namely nirbīja samādhi.

Regarding the subject of pain and its management, Epicurus describes pain as something bad, since its presence moves us away from achieving the aim of life, which is the attainment of aponia and ataraxia. In Patañjali, the concept of pain is found behind the word klésa. Although Patañjali does not make a clear distinction between physical (“pain” of hunger, thirst, illness) and mental (anxiety, fears) in his work like Epicurus, he indirectly alludes to it with the word kleśa5, which has the meaning of mental pain that is responsible for a series of imbalances of a physical and emotional type. 6

Although Patañjali does not make a clear distinction in his work between physical (“pain” of hunger, thirst, illness) and mental (anxiety, fears) as Epicurus did, he indirectly alludes to it with the word kleśa, which has the meaning of mental pain that is responsible for a series of imbalances of a physical and emotional nature.

In sūtra I.307 Patañjali recognizes the existence of physical pain in the form of disease (vyādhi) as one of the obstacles in the process of achieving self-realization. However, the main part of his analysis is found in sūtra II.38 where he enumerates the five afflictions (kleśas), which constitute in reality forms of mental pain. Those are: ignorance, egoism, attachment, aversion and strong desire for life.

The fear of death, which derives as natural effect from Patañjali’s last affliction, is proclaimed by Epicurus as one of the most important mental pains. Even though both philosophers consider the fear of death as one of the afflictions that cause pain, the process of liberation calls each time for a different approach which entails a different account of the soul as well as of death itself.9

Besides the distance that separates their views upon this subject, we cannot but acknowledge their interest in non-attachment to life as an expression of man’s freedom from the bonds of ignorance.

For it is this misconception about the true nature of things10 whether it is called ignorance (avidyā) or kenodoxia that is according to the two philosophers the basic source of that pain. Only the acquirement of true knowledge can really eradicate this illusion.

The way, though, in which each of them defines truth, is related to the different origin of the core of ignorance. For Patañjali, that core is rooted according to sūtra-s II.5 and II.24 in the wrong perception of the transient as permanent, the impure as pure, pain as pleasure, and that which is not the self as the self, and it is the cause of the false identification of the seer with the seen.12.

In Epicurus, contrarily, ignorance comes from the erroneous notion about death and the gods. Notwithstanding its different extensions, main starting point of their thinking remains the firm faith in human intelligence and its ability to break the bonds of illusion and, thus, realize its substance.

The body and the concept of self sufficiency and simple living

At the centre of the dialog between the philosophy of Epicurus and Patañjali lie bodily needs, which, as the two philosophers commonly declare, should be satisfied, insofar as they ensure survival and good health. In his analysis of the term aparigraha (sūtra II.39), Pattabhi Jois suggests eating the amount of food that is necessary for the body’s survival and avoiding desires that exceed this need.13

Of course, Patañjali’s understanding of the body and its needs is not exclusively limited in the sufficient food but deals also with maintaining a healthy body through the choice of appropriate food as well as cleanliness. In sūtra II.4014 , he clearly refers to the need for cleanliness and purification of the body and mind that starts from the outer layer of the body (skin) and reaches its inner parts (blood, organs). Iyengar states that according to Patañjali the body as the soul’s respected shrine should not be neglected15 and stresses the importance of physical health and hygiene for developing a strong body which serves as springboard for the yogi’s spiritual elevation.16

The satisfaction of the needs for food and cleanliness demonstrates in Patañjali an initial categorization of desires. Those are desires which he characterizes as natural and necessary, since they guarantee survival and physical well-being.

In addition, a look at sūtra II.38 sheds light to another distinction of desires with regard to body and its needs. In particular, the term “brahmacarya” that has the meaning of sexual restraint implies that sexual pleasure is recognized as natural but non-necessary according to Epicurus’ example, for it responds to a natural need that defines the body itself17 , yet it cannot ensure health and maintenance in life.

Still, Patañjali doesn’t stop at a qualitative categorization of desires. According to Pattabhi Jois’ explanation of the word aparigraha, he takes a step further by defining the limits of those desires which should not exceed the natural needs. Behind his counsel to receive only the amount of food that is necessary we can detect the activation of a process of contemplation on the real needs as well as an idea about self-sufficiency.

Similarly, Epicurus teaches self-sufficiency as a spiritual exercise of freedom – and not as self-denial – and moreover, as liberation from empty desires and the fear of their non-satisfaction. Freedom as the greatest fruit of self-sufficiency to which the Epicurean sage consciously reaches through the process of reflection on the nature of desire, constitutes the epitome of the epicurean teaching which contends that “genuine pleasure” is not “the pleasure of profligates” but rather the simple satisfaction of a mind and body at peace.18

Liberation from excessive desires19 achieved through the contemplative exercise of distinguishing desires, in favor of which Patañjali appears to speak with the term aparigraha, is the cornerstone of the simple life that Epicurus refers to when he writes to Aelianus “he who is not satisfied with less, is not satisfied with anything” (Various History 4.13).

Behind the principle of non-greediness (aparigraha) one could find Patañjali’s concept of simple life that hasn’t the sense of a strict asceticism but it is founded on Epicurus’ principles of autonomy and moderation.

Behind the principle of non-greediness (aparigraha) one could find Patañjali’s concept of simple life that hasn’t the sense of a strict asceticism but it is founded on Epicurus’ principles of autonomy and moderation.

The writings of the two philosophers provide evidence of their firm intention to define an initiation guide into the art of moral living (kalos zein) that is grounded on the conviction that human life is not a total of moments or episodes but the implementation of a strategy of life.

In essence, it is a sum of views of ethical character that aim at the moral cultivation of the individual in two levels: social (person in relation to society) and individual (person in relation to himself).Those views are summarized in Epicurus in the virtue of prudence and the idea of justice, while in Patañjali in the yama-s and niyama-s.

In the context of the epicurean moral hedonism, in particular, prudence as the “sober thinking that investigates the causes of every preference or avoidance and removes the doctrines20that create disturbance is considered to be the highest among the other virtues, being more important even from philosophy itself.21.

For it teaches, that one cannot live pleasantly, if not virtuously, honorably and justly. This brightness of wisdom, which the epicurean philosopher obtains through the process of contemplation, is the key component of a happy life.

Yet, the concept of pleasure in Epicurus transcends the narrow limits of man’s personal happiness, since it is defined by man’s relationship with the people around him. This aspect involves an idea about justice which is based on the mutual benefit that results from the principle of non-doing harm to or non-being harmed by somebody, and takes the form of social contract22.

Epicurus calls this justice natural, since it satisfies the natural desire for safety. Regardless of whether it has or not the formal validity of law23 , this principle is significant to the extent that it imposes the creation of a field of action, in which the individual defines his own safety and well-being in accordance with and in respect to the limits of the safety and well-being of the other.

The kind of ethics that lies at the core of Epicurus’ ideas of honorable and justice life is also encountered in Patañjali. Similarly, in the philosophy of yoga the course towards the individual’s self-realization is not perceived separately but in relation to the society in which he/she lives.

Basic pillars in this process of self-realization are the omnipotent and universal rules24 of the yama-s and niyama-s. These rules of individual and social conduct, towards which the practitioner owes faith and dedication throughout his life, don’t apply independently but in mutual interdependence.

Hence, the observance, for example, of non-violence or non-stealing cannot be understood without a feeling of contentment or self-study and the opposite. The way in which the value system of yamas and niyamas is structured and intended to function shows that individual and social ethics go hand in hand in Patañjali, constituting an indivisible unity25..

The way in which the value system of yamas and niyamas is structured and intended to function shows that individual and social ethics go hand in hand in Patañjali (as in Epicurus), constituting an indivisible unity.

Apart from to its moral foundation, it has been argued that Epicurus’ philosophy, like Patañjali’s yoga, also has a therapeutic character26 insofar as it contributes to the extinction of mental diseases that derive from the afflictions (kleśas) according to Patañjali or the fear of death according to Epicurus. Patañjali, of course, never goes so far as to compare philosophy with medicine and the philosopher with a doctor, as Epicurus did27.

Let alone proceed to design specific therapeutic strategies based on the medical model like its ancient Greek counterpart28. Nevertheless, in both cases the idea of healing as a process of restoring spiritual balance and experiencing the true greatness of the soul has not only a central position but also a catalytic role in the realization of their philosophical vision.

Notes

[1] Alga, K., Barnes, J., Mansfeld, J., Schofield, M., The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy, Cambridge: University Press, 1999, p. 651-657

[2] Alga, K., Barnes, J., Mansfeld, J., Schofield, M., ibid., p. 659

[3] See Iyengar, BKS, Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, Thorsons, 1996, p.115

[4] 2007, “Inside the Yoga Tradition”, Integral Yoga Magazine, p.20

[5] Nakamura, H., A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, 1989, p.772

[6] Iyengar, BKS, Core of the Yoga Sūtras, HarperThorsons, 2012, p.79

[7] See Iyengar, BKS, Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, Thorsons, 1996, p. 83

[8] See Iyengar, BKS, op. cit., p. 111

[9]See Kechrologos, Ch., 2010, “The Epicurean management of the fear of death and its transfer to today”, Philosopher, pp. 66-72

[10] Hariharananda, SA, Yoga Philosophy of Patañjali, SUNY Press, 1984, p. 116

[11] Iyengar, BKS, Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, Thorsons, 1996, p. 114

[12] Iyengar, BKS, op. cit., p. 134

[13] Pattabhi Jois, in his analysis of the term “aparigraha” in sutra II.39, refers to securing the food necessary to sustain the body and avoiding desires that exceed this need. See Jois, Sri.KP, Yoga Mala, North Point Press, 2010, p. 93 and Jois, S., The Sacred Tradition of Yoga, Shambhala Publications, 2015, Chapter 7

[14] See Iyengar, BKS, Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, Thorsons, 1996, p. 153

[15] Iyengar, BKS, Yaugika Manas, Yog, 2010, p. 93

[16] Iyengar, BKS, Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, Thorsons, 1996, p. 154

[17] In contrast to vain (empty) desires, in which there is no limit to their satisfaction.

[18] Rosenbaum, S., 1990, “Epicurus on pleasure and the complete life”, Monist, 73(1), 21, Retrieved October 4, 2007, from Academic Search Premier database

[19] See Long, AA, From Epicurus to Epictetus, Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 202

[20] Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus or On Life, translated by Leonidas A. Alexandrides, Friends of Epicurean Philosophy “Garden of Athens”, October 2013, p.5

[21] See Mitra, A., 2015, “Epicurean Ethics: A Relook”, American International Journal of Contemporary Research, Vol. 5, No. 1, p. 99

[22] See Thrasher, JJ, 2012, “Reconciling Justice and Pleasure in Epicurean Contractarianism”, Ethic Theory Moral Prac, Springer

[23] See Chroust, AH, 1971, “The Philosophy of Law of Epicurus and the Epicureans”, American Journal of Jurisprudence, Vol. 16: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ajj/vol16/iss1/3

[24] See sutra II.31, Iyengar, BKS, Light on the Yoga Sūtras of Patanjali, Thorsons, 1996, p. 143

[25] See also Krishnananda, S., Yoga as a Universal Science, The Divine Life Society, pp. 176-190

[26] See Carlisle, C., Ganeri, J., Philosophy as Therapeia, Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 219

[27] See Warren, J., The Cambridge Companion to EPICUREANISM, Cambridge University Press, 2009, p. 249-265

[28] See Warren, J., op. cit., p. 249